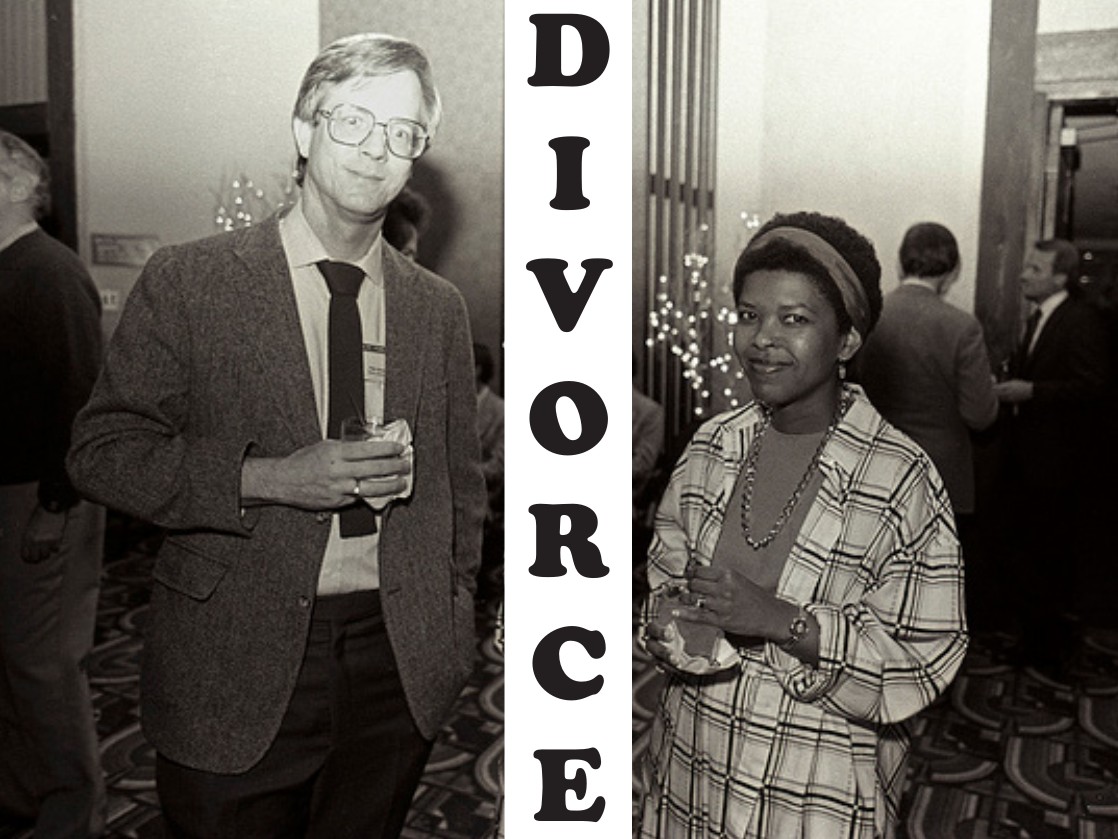

Peter Norton, founder of the company whose ubiquitous computer software bears his name, sold his firm in 1990 to devote himself to philanthropy. With his wife, Eileen Harris Norton, he ran the Peter Norton Family Foundation, which has given heavily to arts organizations and some social-service groups. In 2000, Peter Norton filed for divorce. As often happens when a large fortune is at stake—Norton’s assets exceeded $100 million—the case was heavily litigated over a period of years. Eileen won the first round when a judge ruled that roughly 87 percent of the proceeds from the sale of the software company were to be considered community property, subject to equal division. One issue not on the table, however, was what would happen to the foundation.

This is an especially tricky subject. A foundation, strictly speaking, is not a marital asset—once money is donated, it is no longer under the personal control of the benefactors. Yet this is a grey area because influence over the foundation is, in a way, a fringe benefit of a marriage. That’s why many divorce attorneys will put the family foundation on the table during negotiations even though it is not a financial asset. “Say there’s a $100 million foundation,” explains William D. Zabel of Schulte Roth & Zabel in New York, a leading divorce lawyer to the rich and famous. “The husband says to the wife, ‘That’s it, you’re out, you have nothing more to say about it.’ I’d take that case in a minute.”

Virginia Esposito

Virginia EspositoThe confluence of two factors—the astonishing growth in the number of family foundations and a national divorce rate that continues to hover near 50 percent—suggests that family foundations will increasingly become an issue in divorce. “People are establishing foundations at a younger age,” says Virginia Esposito, president of the National Center for Family Philanthropy. “Everything in this founder generation is new. And changes in the family, happy or otherwise, are inevitable.”

Established in 1989, Norton's foundation had a market value of some $26 million by the end of 2002, a year in which it distributed more than 100 grants totaling $3 million. The biggest gifts went to the California Institute for the Arts, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Studio Museum of Harlem, and New York’s Symphony Space, which named its concert hall for Norton following a $5 million pledge. A one-time Buddhist monk, Norton has also made some offbeat philanthropic gestures, such as buying the notoriously personal letters written by the reclusive author J.D. Salinger to Joyce Maynard at auction from Sotheby’s for $156,000 and then returning them to their author.

After the divorce, a court order split the foundation 60/40 between the two, with, according to its 2011 IRS filing, a “substantial contraction.” A final return representing 2012 would be prepared, indicating that the foundation, which reported assets of only $50,000 in 2011, would shortly be out of business. Both Peter and Eileen continue to serve as trustees, along with Anne Etheridge, who is executive director.

Of the possible paths for family foundations caught in the middle of a divorce, some are exceedingly civilized. Virginia Esposito remembers an instance where both parties stayed on the board after the split. “They talked about it and decided that what they were doing transcended their personal problems, and now they seem to be doing just fine.” In another case, not only did both exes remain on the board, they were joined by their adult children and a new wife. “They realized the foundation was a part of their selves and have stayed focused on the work,” Esposito says. “It may not be personal property, but it’s part of their personal responsibility.”

Sometimes it’s important to give the participants “some breathing room,” she adds. “It may just be a matter of getting past the immediate difficulties. And you have to factor in the possibility that feelings might change. You could have the husband say, ‘I’m not that involved; you go on ahead with our adult children.’ Then, a few years later, he realizes there’s a space in his life and he wants to be more involved in his community.”

Of course, not everyone can be so calm and rational in the midst of divorce, and one option at the other extreme is to split the foundation in two. This isn’t terribly difficult as a technical matter, although there is some lawyering involved. “The basics aren’t that hard, but for people in that situation everything’s a big deal,” says Jerry J. McCoy, a Washington-based attorney specializing in charitable issues. “She says, ‘Most of the money was from my family,’ and he says, ‘But I tripled it in the boom,’ and she says, ‘But you tripled my money.’ It often degenerates into bitterness and that inability to get along.”

Karen Greene, who heads family foundation services at the Council on Foundations, recalls a number of occasions when a giving vehicle was rolled into two separate ones. For example, Norman Waitt Jr., who founded Gateway Computers with his brother Ted, later established the Andrea and Norman Waitt Jr. Foundation. After the Waitts’ divorce, the fund split into Norman’s Kind World Foundation and Andrea’s Messengers of Healing Winds Foundation.

Raoul Felder

Raoul FelderBut the same effect can be achieved more informally. “We frequently make claims that the wife has the right to direct a certain amount of foundation spending after the divorce,” says Raoul Felder, the dean of New York divorce lawyers. “As part of the settlement, the husband gives from his foundation to, say, the New York Community Trust, where she can set up something and control the spending. This is happening as people are getting more sophisticated.”

“Money is a socially prestigious weapon,” says Bill Zabel. “[Women] serve on boards where they have to make a $50,000 or $100,000 annual contribution. Take away that money and you’re causing tremendous harm to her social life. That’s why, in a majority of substantial divorce cases with a foundation, the departing spouse usually has an issue about how to share in the distribution. You can have a foundation giving away a million a year, and she might say, ‘I need $200,000 of that to keep up my contributions.’ So as part of the deal, you might give her the right to designate that amount. It’s usually done as a side letter, not as part of the public document, and the wife isn’t usually on the board after that – they want her out of there.”

Zabel has even seen foundations used for underhanded maneuvers in this realm: “Say a guy has $60 million, has been married 30 years and wants a divorce. So, he transfers $10 million to his foundation and says, ‘We have $50 million to split.’ Does he negotiate and give her certain rights to distribute that $10 million? Or does she say, ‘I should get $30 million, since he gave that money away knowing he would divorce me.’ It’s all arguable and negotiable and litigable. I don’t believe anyone’s ever litigated it—I’ve threatened to and settled—but it probably will be someday.”

The best way to avoid these sticky scenarios, experts say, is to think things through in advance. “When setting up a family foundation, you need to define what you mean by ‘family,’” advises Mary Philips of Grants Management Associates, Boston-based philanthropic consultants. “Set the criteria upfront so it doesn’t become personal. Make it clearly written: in the event of divorce, the divorcing spouse goes off the board—or not. Do we want only lineal descendents? Think of board eligibility in terms of your goals and the experience you want rather than who you want.”

“Ideally, families should treat eligibility in a fairly rigorous way,” says Karen Greene. “This applies not only to the founders, but to later generations. It seems inconceivable when it’s just you, the wife and the kids, but go down a couple generations and you’ve got 20 or 30 people. Someone’s divorced, another one never shows up at meetings. Do you just want lineal descendants? What about adopted children, stepchildren, offspring of gay and lesbian partners? Should your foundation exist in perpetuity, given how much families can change? It can be a ticklish situation, very uncomfortable if you’re the in-law who becomes the ‘out-law.’ It’s always better to make policy in the abstract, but you can’t foresee every circumstance. I remember one gentleman who came up and asked me, ‘How do I keep my daughter-in-law and get my son off the board?”

The Nortons are only one of many examples where philanthropists must think through all the implications of their divorce.