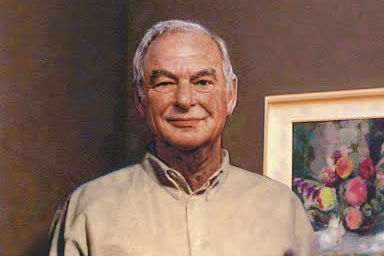

It’s a sunny July morning about a decade ago, but Gerry Lenfest is smiling like a kid in December. A deliveryman has just deposited a six-by-four-foot plywood crate on his office floor, and Lenfest, who at the time was a hale septuagenarian, is going at it with a Phillips-head screwdriver. “Watch your fingers,” cautions his wife as he pries the crate open, and soon the entire staff of his foundation—three people, to be exact—has taken over the job. Lenfest stands back, still smiling, and watches.

Moments later, a million-dollar painting by Jacques Villon (Marcel Duchamp’s older brother) is standing splendidly by the front door, and the assembled group “oohs” and “ahhs” appreciatively. “It’s like Christmas here all the time,” says Lenfest’s accountant. “It’s always something coming in.”

And going out. In 2010, Forbes estimated Lenfest’s worth to be $430 million, and his primary activity these days is giving it away. When The Philadelphia Inquirer—which Lenfest ended up purchasing in its entirety last year in the interest of keeping the paper locally owned and operated—reported that he planned to “die penniless,” thousands of people wrote to him, looking for help with their bills, businesses and medical problems. Most wanted just a few thousand dollars, and Lenfest could have played Santa Claus to them all without denting his fortune. It’s true that he wants to empty his accounts. But he doesn’t want to do it that way.

Harold Fitzgerald Lenfest grew up in Scarsdale, N.Y., and Lambertville, N.J., the son of a shipping-industry executive who worked by the Manhattan docks. As a young lawyer, Lenfest served for a time as an assistant counsel to Walter Annenberg, the media magnate and philanthropist, and the seeds of his fortune were planted in 1974, when he bought a handful of tiny cable TV franchises from Annenberg and went out on his own. Sleeping on couches, he stayed one jump ahead of his creditors and slowly built a highly profitable business encompassing regional clusters of cable systems, mainly in rural and suburban Pennsylvania. In 2000, he sold Lenfest Communications to Comcast Communications for more than $7 billion. His personal take on the deal was $1.2 billion.

When he was growing up, he recalls, his family wasn’t poor, but “we weren’t that wealthy that we had to face the responsibility of what to do with it.” Today, as he considers the meaning of a billion, he is reminded of a long-ago meeting with another wealthy man, Roland Harriman. “When I practiced in New York, the firm represented the Harrimans,” he says, sitting in the boardroom of his offices high above the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia. “He liked me, and invited me up to Harriman, New York, the night before they opened their Goshen racetrack. He had a few drinks and said, ‘You know, Gerry, everyone envies me because I’m so rich. Well, when you’re as rich as I am, it isn’t fun, it’s responsibility.’

“I didn’t feel sorry for him at the time,” Lenfest continues with a chuckle, “but I now recognize that being a billionaire is a responsibility. What do you do with a billion? Do you hoard it and die with it? Do you give it away? I think if you have that kind of wealth, you have to be responsible, and figure out what you can do with it.”

Lenfest learned about responsibility long before he was rich. For two years in the 1950s, between college and law school, he commanded ships for the U.S. Navy. His first was a destroyer escort out of Bayonne, N.J., the USS Coates. “When I took over that command, it was the worst ship in the squadron,” he recalls. “The first step was to challenge [the crew]. In January, we were in Long Island Sound, with five other ships. We had been scheduled for a gun shoot, and it was a cold, cold wintry day, with high winds. We were the only ship that went out and did the gun shoot. All the others said, ‘It’s too stormy,’ and I said, ‘We’re going.’ And we went. And we shot. And that was the beginning. Two years later, we won every award in the whole Atlantic fleet.”

Today, Lenfest still challenges. He gives millions to fund prep school and Ivy League scholarships for students from rural Pennsylvania, but the students must maintain their grades to their schools' satisfaction. He gave $50 million to the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the condition that it keep its perennially unbalanced budget in the black. He supported global-warming research with a $15-million gift to the Earth Institute at Columbia University, where he currently serves as a trustee, on the condition that it cannot spend the money on routine costs like maintenance or phone bills. And he's referred to his purchase of the Philadelphia Inquirer as the most important thing he's ever done.

“He’s no pushover,” says Margaret Chew Barringer, founder and chairman of the American Poetry Center, a Pennsylvania arts organization that lists him as a major benefactor. “We asked him for some matching grants, and he made us prove that we had other sources lined up so that we wouldn’t have to keep coming back to him for more. He can be very hard-headed. But once you get past his demeanor as a businessman, he really has a heart of gold. He has the integrity of an artist. You can’t fake that.”

Lenfest didn’t get serious about philanthropy until he sold Lenfest Communications; then, cash in hand, with an eye toward doing something in education, he quickly learned that it would be easy to spend a lot without getting a lot. “I noticed that Walter Annenberg, my former boss, had given away five hundred million [for educational initiatives] and, in a sense, it went down the drain with no real impact.” Some of the mentoring models he saw seemed effective, “but mentoring people means we’d have to hire people, and follow young people through high school and into college, and it seemed like more of an infrastructure than we wanted to have.”

So he looked for a leaner way to do business, and he found it by following the pattern he had established as a businessman: set goals and conditions, delegate responsibility and stay out of the way.

In 2000, Lenfest gave a long interview to an industry Web site called The Cable Center, explaining how he had built his company. “I really owe a lot of my success in life to people that have worked for me,” he said at the time. “I’ve always had a sort of philosophy of individual responsibility. We never had many committees—or any committees—and we would put people in charge of cable systems in regions and pretty much let them run it as they saw fit .... As long as you made them feel that this was their area, their responsibility, and you gave them the freedom to make decisions and do it right, in most cases it worked out very well. So, you learn how to achieve through others.”

His philanthropy works the same way. Lenfest’s main philanthropic vehicle, the Lenfest Foundation, was originally endowed with $100 million and continues to be managed by a small staff. Once he and his wife Marguerite have decided what they want to fund, they delegate almost all the responsibility for the projects’ success to their grantees. He doesn’t hire program officers or evaluation specialists. Consultants fill the gaps when needed. Conditions built into the grants themselves ensure that the money doesn’t dribble away.

What Lenfest does, in effect, is pick targets and let the grantees aim. “It’s like on that ship. The gunnery officer’s better at gunnery than I am,” he says. “Don’t ask me how to do it—you’re the gunnery officer. You’re good at what you do. You do it.”

There’s a story about Lenfest that captures his tough side. Early in his career, he owned a tiny cable franchise near Binghamton, N.Y., that served about 1200 subscribers. The franchise came up for renewal, and Lenfest wanted to raise his rates. The subscribers, of course, didn’t want to pay more. Lenfest went for a showdown at the city council. “They had tough attorney, and he stood up and glared at me. ‘I understand you’re here to ask for that goddamned rate increase’,” Lenfest remembers. “I said, ‘No, I’m here to tell you that we’re taking down our lines and stopping service to your community’.”

Was he serious? Would he have cut down the lines? “Yeah, I was serious,” Lenfest replies. “But I didn’t think it would happen. That town was down the hole.” He chuckles. “They had no reception [of TV signals without cable]. The next day we had our increase.”

Today, being tough means saying no. His gifts fall in three basic categories—art, science and education—each of which is broad enough to ensure a constant stream of applications. “For everything we support, we turn down a hundred requests,” he says. “You have to learn how to say no. You have to decide what you think will have the most impact and do the most good.” Major recipients include Lenfest’s schools (his prep school, Mercersburg Academy; his college, Washington and Lee University; and his law school, Columbia), Pennsylvania arts institutions (including the Kimmel Center, the Curtis Institute, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the James A. Michener Art Museum) and environmental programs like the Earth Institute.

But along the way, Lenfest decided that the main way to make sure that his money can “do the most good” is to get it out of his bank account. He has long said that his foundation will cease to exist within 10 years of his death (or his wife’s, whichever comes later). In 2013, Lenfest stepped down as the foundation’s chairman—although he remains a board member—and his newly appointed executive director, Keith Leaphart, will head the eight-member board through June of this year. In 2014, Lenfest and a business partner bought out then co-owner of the Inquirer, George Norcross, after Norcross helped dismiss a much-loved editor, Bill Marimow. (Marimow refused to fire senior staff per Norcross’ wishes.) Lenfest subsequently become sole owner of the paper. By almost any account, his stake in the Inquirer will net him up to a $10 million loss in the interest of maintaining the paper’s local integrity.

Lenfest wants his legacy carried on in subtle ways: in the work of the institutions he and his wife have supported; in the philanthropy of his three children (who established their own foundations with their share of the sale of Lenfest Communications) and, he hopes, in the lessons that his fellow philanthropists glean from his actions.

“I read about the Philadelphia Orchestra’s four-million-dollar deficit,” Lenfest says from his seat in the boardroom, the new Villon now leaning against the wall behind him. “Four million per year! Annenberg [the Annenberg Foundation] has given them a gift, conditioned upon their balancing the budget.” Now the old commander’s eyes brighten and he laughs quietly. “They said, ‘We got the idea from you, Gerry.’”