Should charity begin at home?

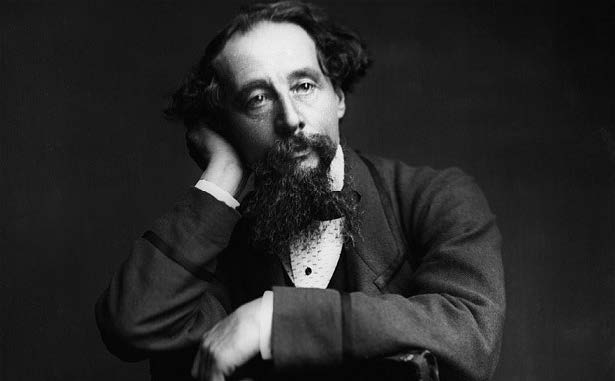

Yes, in the strong opinion of Charles Dickens, who used Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House to blast what he termed “telescopic philanthropy.”

When we meet Mrs. Jellyby, she is busily engaged in dictating letters to her ink-stained wretch of a daughter on behalf of a project to settle some two hundred impoverished British families in Borrioboola-Gha, on the left bank of the Niger, where they are to cultivate coffee and educate the natives. Mrs. Jellyby’s home is squalid: Dinner is nearly raw and four envelopes float in the gravy, her innumerable children are virtually abandoned, and she herself is a mess—her hair needs brushing and her dress gapes in the back, revealing a lattice-work of stays “like a summer house.” But Mrs. Jellyby is blithely oblivious to the misery around her, the narrator writes; her handsome eyes “had a curious habit of seeming to look a long way off, as if . . . they could see nothing nearer than Africa.” When her oppressed daughter escapes her clutches to marry, the long-suffering Mr. Jellyby sends the girl off with one piece of advice: “Never have a mission.”

Like many of Dickens’ greatest characters—think Scrooge or Mr. Micawber or Miss Havisham—Mrs. Jellyby is regularly invoked by modern writers as a cautionary figure. Google “Mrs. Jellyby,” and you’ll see references on issues ranging from Gaza to coal mining. George Will accuses Arne Duncan, President Obama’s Secretary of Education, of a Jellyby-like indifference to the education of low-income children “within sight of his office” on Capitol Hill while pursuing loftier goals. Another writer, in a piece in Salon titled “Mrs. Jellyby Goes to Washington,” grumbles that the administration should focus on jobs, not global warming. A Christian scholar, arguing that Mrs. Jellyby and her like are motivated by anger, recalls an activist who nearly starved the office cat because he was morally opposed to the domestication of animals.

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.But can we really learn from Mrs. Jellyby? Let’s remember that Dickens subscribed to the Victorian view that a woman’s place was in the home and was quick to condemn any woman who failed to be the “angel of the house.” (Never mind that Dickens himself was a less than exemplary husband and father.) It’s no accident that, at the end of Bleak House, Mrs. Jellyby, having discovered that her African king wanted to sell everybody— “who survived the climate”—for rum, takes up as her next cause the rights of women to sit in Parliament, a “mission” that Dickens evidently found as preposterous as Borrioboola.

While few charities are as ill-chosen as Mrs. Jellyby’s, philanthropy inevitably involves tradeoffs. Spending vast sums to fight AIDS in Africa can mean fewer funds for needy families closer to home; efforts to improve the conditions of the homeless here can result in less money for pre-school. Dollars, like time and energy, are finite. In the end, for philanthropists, the issue is arguably not how remote the cause but how deserving.