One collects Fabergé eggs, another acquires supermodels, and a few more invest in football and basketball teams. But whatever their avocations, Russia’s oligarchs have two things in common; their wealth is unimaginably vast and their ties to President Vladimir Putin are undeniably strong.

This situation has produced what could be called the Russian paradox. The advent of a free-market economy has led to an explosion in private wealth and according to Forbes, Moscow is home to 84 billionaires worth a total of $360 billion—and with that an unprecedented boom in philanthropy. But, increasingly, under Putin’s guidance, the philanthropy of these new tycoons resembles nothing so much as an extension of the national government.

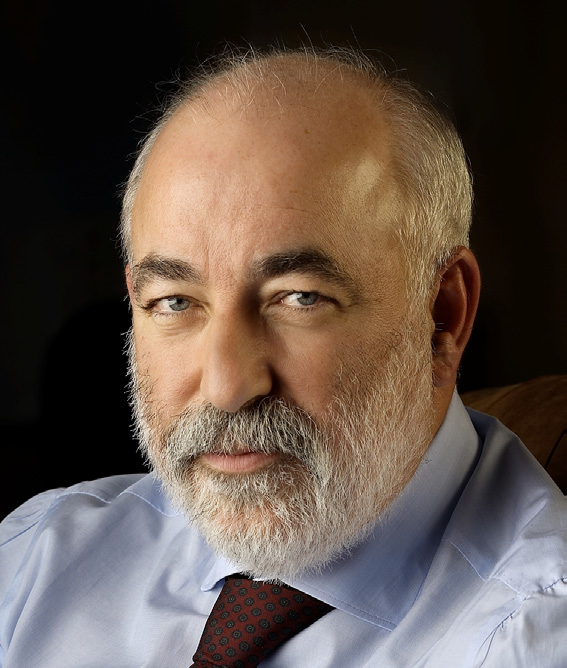

Viktor Vekselberg

Viktor VekselbergThe roll call of Russia’s philanthropists is, predictably, a Who’s Who of the country’s most affluent and successful: Alisher Usmanov (possibly the richest man in Russia), Roman Abramovich, Vladimir Potanin (who in 2013 became the first—and, so far, only—Russian billionaire to sign the Giving Pledge), Dmitri Zimin, Mikhail Prokhorov, Mikhail Fridman, and the husband-and-wife teams of Dmitri Zelenin and Alla Zelenina, and Viktor Vekselberg and Marina Dobrynina. (It was Vekselberg who spent more than $100 million in 2004 to triumphantly return the 194-piece Forbes Fabergé jewellery collection, including nine exquisite eggs, to Russia.)

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Mikhail KhodorkovskyNoticeably absent from the list are two prominent critics of Putin: Mikhail Khodorkovsky, formerly the richest Russian, now living in Europe, and the late Boris Berezovsky, both of whom could legitimately claim to be forefathers of modern Russian philanthropy.

The pattern is clear. If you garnered vast wealth thanks to the break-up of state-owned assets in the 1990s, then you owe, big time. Campaigning in 2012, Putin frequently noted that he was considering a special tax on entrepreneurs who had benefited from acquiring state assets at “unfair prices.” Whether he does this or not (it seems unlikely), he clearly remembers his debtors. And he has not been shy about collecting.

From dropping tycoons into the governorships of obscure, dilapidated regions to strong-arming cash donations for projects of international resonance, the former KGB chief maneuvers some of Russia’s private wealth to the places he sees fit. Subtly and not so subtly (Khodorkovsky, after all, served ten years in a Russian prison for fraud and tax evasion before being released in 2013), the once-and-seemingly forever President has made it clear that, in return for their continued economic and even personal freedom, Russia’s capitalists must pay.

By all accounts, they paid handsomely to fund last year’s Sochi Winter Olympic Games, reportedly the most expensive Olympics ever, with an estimated price tag of $50 billion. A major infrastructure program has been announced for the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, and it’s certain that it will generate both lucrative contracts and donations from grateful businessmen.

Such donations add up. In 1998 individual giving in Russia amounted to a piddling $200,000. From 2010-12, 10 of Russia’s 15 richest gave away $1.3 billion, according to Bloomberg Markets. It is an astonishing amount but there’s lots more where that came from: The combined wealth of the 10 stood at $127 billion, as of April 2013.

When compared to the West’s big donors, the figures appear a little less impressive. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, backed by Warren Buffett, gave away $6 billion of the trio’s combined $124 billion wealth in 2011 alone. However, Americans have had more time to perfect the nuanced art of modern philanthropy. What’s more, such lists fail to acknowledge the regional development underwritten by Russia’s oligarchs.

Roman Abramovich

Roman AbramovichFor example, Roman Abramovich reportedly gave $310 million to charity in 2010-12, but that doesn’t include the $164 million that Evraz, a steelmaker Abramovich owns in part, spent on social projects in its operations area in the same period. Similarly, Mettalloinvest, which Usmanov controls, gave $260 million to local services and social programs in 2010-12, on top of $247 million in personal donations.

Public office is a favourite tool of Putin’s. Fridman, Abramovich, and Zelenin have all taken a turn in the last 15 years, and it isn’t cheap. Abramovich is reported to have given or invested $2.5 billion in local services and charitable initiatives in the remote Russian Far East region of Chukotka, where he was Governor for eight years. Chukotka seems to have benefited. From 2000, Abramovich’s first year in office, to 2006 average salaries rose in the region from $165/month to $826/month. Housing and healthcare also improved with Chukotka boasting the highest healthy birth rates in Russia during Abramovich’s tenure.

Putin tweaked the rules in 2005 to facilitate this kind of appointment and now has personal responsibility for the hiring and firing of the governors for all 83 regions. As a result, when Abramovich made noises that he’d had enough of the cold of Chukotka after one term, Putin insisted otherwise. Although Abramovich was finally allowed to resign in 2008, his gift keeps giving: In 2010-12 he gave $98 million to the Territoria and Pole of Hope foundations, which support humanitarian work in Chukotka. And even several years after Zelenin left the governorship of Tvor Oblast, his wife raised more than $300,000 per year for their “A Kind Start” charity.

This type of state-directed philanthropy has elements of the old Russia. For centuries under the czars, charity was linked to the church and the largesse of the more enlightened aristocracy. The 1800s saw the rise of individual philanthropists like Baron Horace Gunzburg, and wealthy families such as the Morozovs and Mamentovs, who supported orphanages, hospitals, museums, and the arts. The Bolsheviks halted giving when they took power in 1917, and for more than seven decades philanthropy was banned. Soviet control enforced donations to officially selected charities and required millions to “volunteer” their time.

But with perestroika, new private enterprises were born, and they immediately began making donations to charity. By 1998, more than 75% of Russian companies were engaged in corporate philanthropy, although the giving was concentrated among the biggest companies. Even in 2004, more than half of Russian philanthropy came from just 20 corporations. Money went to fund the Olympic team, student exchanges and, under new accounting standards, certain business costs inherited from the Soviet era, such as staff housing. Lukoil, for example, made charitable contributions to train oil-industry recruits as well as to support young children, old soldiers and disaster victims, religious groups, and cultural endeavors.

Vladimir Potanin

Vladimir PotaninVirtually all giving was by companies, rather than individuals, until 2000, when Potanin (who later invested in the Ford Modeling Agency in the US) launched Russia’s first private foundation. (Not until 2011 were individual charitable donations finally made tax deductible.) A year later Khodorkovsky established the Open Russia Foundation, with Lord Jacob Rothschild and Henry Kissinger among its trustees, and with the goal of fostering a democratic society with activist citizens demanding a functioning state, an accountable government, and transparent human rights.

Before he was arrested in 2003, Khodorkovsky observed that his country had squeezed the progress of generations of the Rockefellers and Morgans, from robber barons to philanthropists, into just five years. Khodorkovsky himself was an exemplar of such rapid progress. Once a Communist Youth League activist, he did well in commodities and banking in the early 1990s. Subsequently, he bought cheap privatization shares and in 1995 gained control of the state oil giant Yukos for $350 million, a fraction of its market value. It became the world’s fourth largest oil company, with a one-time net worth of $15.2 billion. Until prison cut short nearly all of his activities, Khodorkovsky was putting $200 million a year into Open Russia.

As Khodorkovsky’s dramatic trajectory suggests, sizable forward movement in Russian civil society is often followed by an equally sizeable retreat. In 2012, Putin demanded that all Russian institutions receiving financing from foreign sources be registered as “foreign agents,” a regulation that crippled many of the NGOs operating there, increasing the need for Russian philanthropists to step up to the plate. Now sanctions imposed by the West in response to conflict in Ukraine are starting to take their economic toll. How this will play out for Russia’s oligarchs and their newfound philanthropy remains to be seen.